If you missed parts one and two of this blog series be sure to give them a look. We cover the process of building our cabinet boxes and hardwood face frames as well as the procedure of milling rough sawn lumber into dimensioned stock.

The next step of our project is to build the raised panel cabinet doors for our lower cabinets. To do this we will need a router table. If you don't have a router table in your shop I highly recommend looking into adding one. In our shop we use the Professional Router Table Package RTP-103.

In addition to a router table we also need a set of rail-and-stile router bits. I also recommend investing in some Parallel Jaw Clamps like those from Irwin. Infinity offers rail-and-stile router bits in several different designs and profiles making it easy to achieve the right look for your project. We chose to build our cabinet doors with the Infinity 2 piece rail and stile set in Art Deco profile (91-506) and the matching Art Deco Raised Panel Bit (90-511). These bits are available in a 3-piece package (00-109).

Building a raised panel door is not difficult. The first step is to determine the size door that is needed. For our cabinets we need doors that measure 17" wide by 23" tall. With these dimensions we can figure out the sizes of the individual pieces. First we determine the length and width of the stiles (vertical pieces) and rails (horizontal pieces) that make up the door frame. We decided that the frame should be made from 2-1/2" wide pieces. This means that our stiles will be 23" long and 2-1/2" wide. The rails will also be 2-1/2" wide and the length can be determined with a little math.

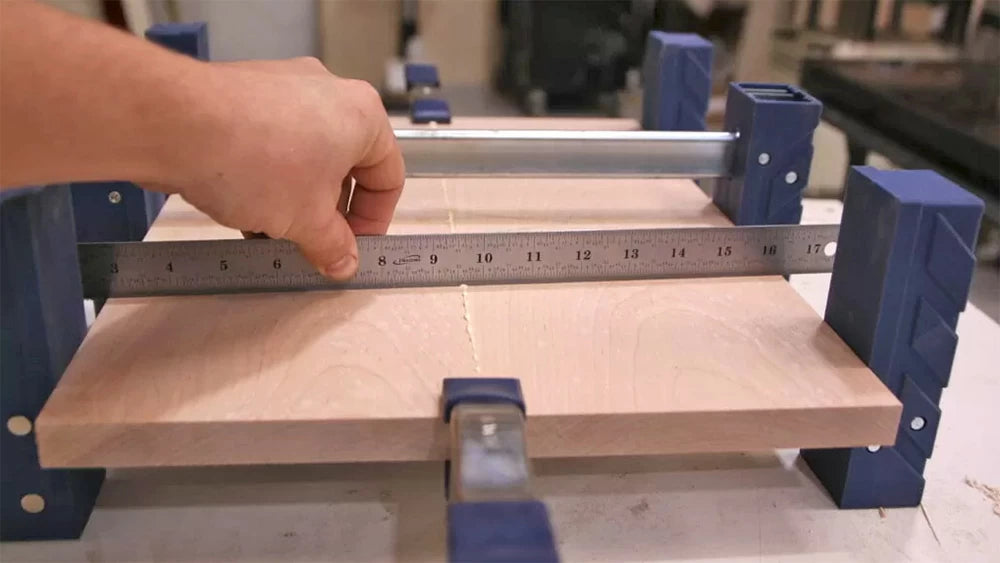

To figure the length of the rail we take the finished width of the door 17" and subtract the total width of the two stiles (5"). Then we add back the amount that the rails and stiles need to overlap. With the Infinity 91-506 rail-and-stile bits, this is 7/16" so we add back 7/8" to the length of the rails for a final dimension of 12-7/8"long by 2-1/2" wide.

Because we want the panel to float in the frame, we need to leave a little room for expansion and contraction. I also like to use space balls in my panel doors as they keep the panel centered in the frame while letting the panel move when needed without binding. I leave 3/16" in each groove for the space ball, this puts the panel under a bit of tension without being too tight. Everything considered our panels will end up being 12-1/2" wide by 18-1/2" long. We use the same basic math that we used to determine the lengths of the rails and stiles to determine the size of the panel. in my case using space balls I just need to make sure that the panel tongue fits into the groove in the frame 1/4" all the way around. We also chose to back-cut our raised panels. Since we're using 3/4"-thick stock, back-cutting centers the panel in the thickness of the frame, making the back and front faces of the panels and frames flush.

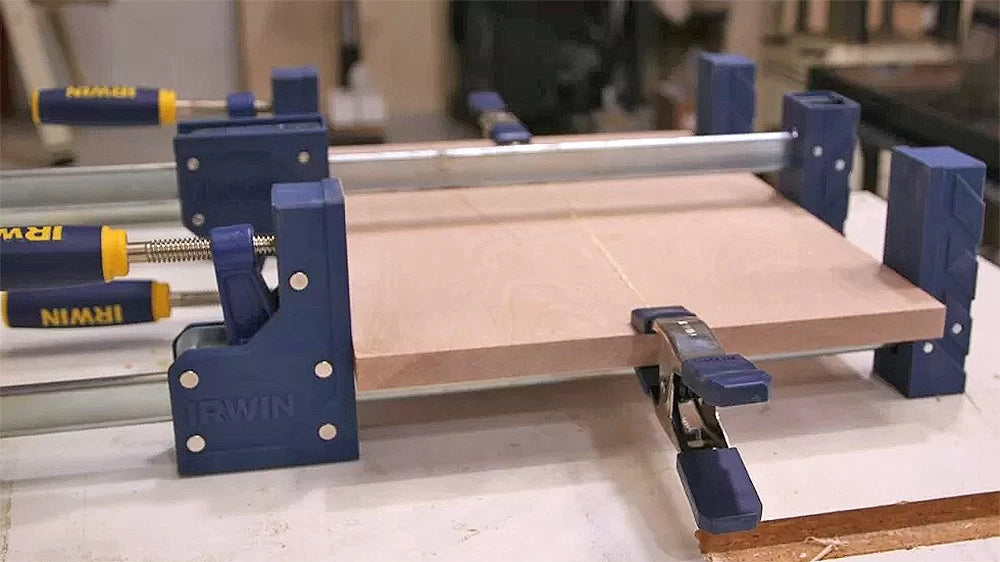

To create a panel wide enough for the cabinet door frame, we glued up two pieces of hardwood. Titebond Original is my glue of choice for this type of joint. I use a spring clamp over the joint at each end of the panel to keep the two pieces aligned as you apply clamping pressure using the parallel-jaw clamps.

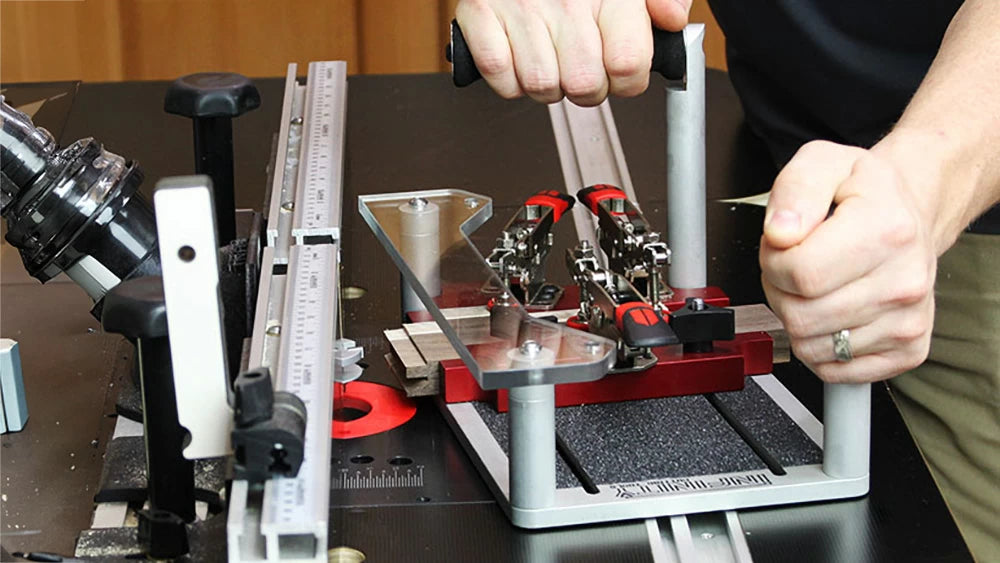

While the glue is drying on the panels I start milling the parts for the cabinet door frames at the router table. I start with the rails first using the rail cutter from the rail-and-stile router bit set. This makes the "coping" cut on the ends of the rails that mate with the stile profile later on. For this task, I use the Infinity Professional Coping Sled (COP-101).

Before I start I mark all my pieces so I don't accidentally rout with the wrong side up. I mill the ends first because if there is any tear out, the stile cut will help clean them up. The coping sled makes quick work of milling the rails and ensures a safe and accurate cut.

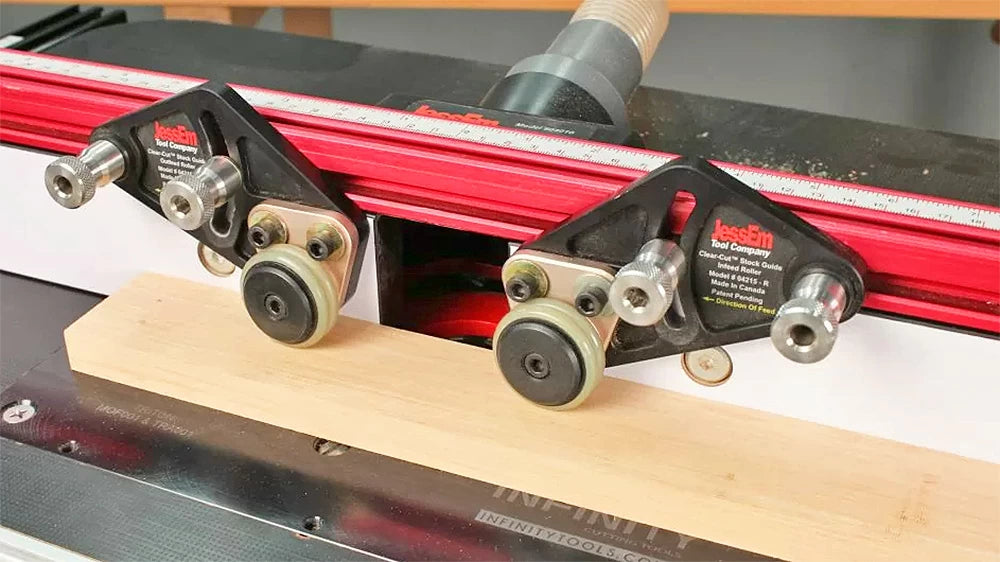

With the rail ends cut, both the rails and the stiles need to receive the stile cut, this is the cut that creates the profile and makes the groove for the raised panel. To make this cut safely I like to use the JessEm Clear-Cut Stock Guides (RTF-SG1) for the router table. They provide anti-kickback protection and hold the workpiece down and pull it toward the fence at the same time. This not only improves accuracy and cut quality but also can extend the life of the router bit by reducing vibration that can damage to the cutter.

With the frames complete it's time to mill the panels. I start by installing the raised panel bit in the router and milling the panel in a few passes. I start with the end grain and rotate the panel counter-clockwise until the panel has been milled on all four sides. This method helps reduce tear out. As I mentioned before, I used a back-cutter router bit to mill the back of the panel so that it can slide into the groove in the frame. I make the back cut just like I did the panel-raising cut (in several passes) being careful not to cut too deeply or the panel will be loose in the frame. I take my time on the first panel and dial in the bit height until the frame slides into the frame without forcing.

Cabinet door assembly is pretty straightforward. I use space balls in the frames to keep the panel centered and allow for expansion and contraction. I find that six will do the trick: One at the top and bottom of the frame with two on each side. The best clamps for door assembly are parallel-jaw clamps. Their design helps keep the door square.

One tip I learned from my time working in cabinet shops is to make one extra rail. The rail has the rail cut, stile cut, and edge detail and is saved to be used as a perfect matching setup block. In the event that you miscounted how many doors you need, the project scope changes midstream, or a door gets broken several years down the road, this little block is a lifesaver. Choose a scrap piece of stock that is a good representation of the project, in other words don't pic an ugly off-cut.

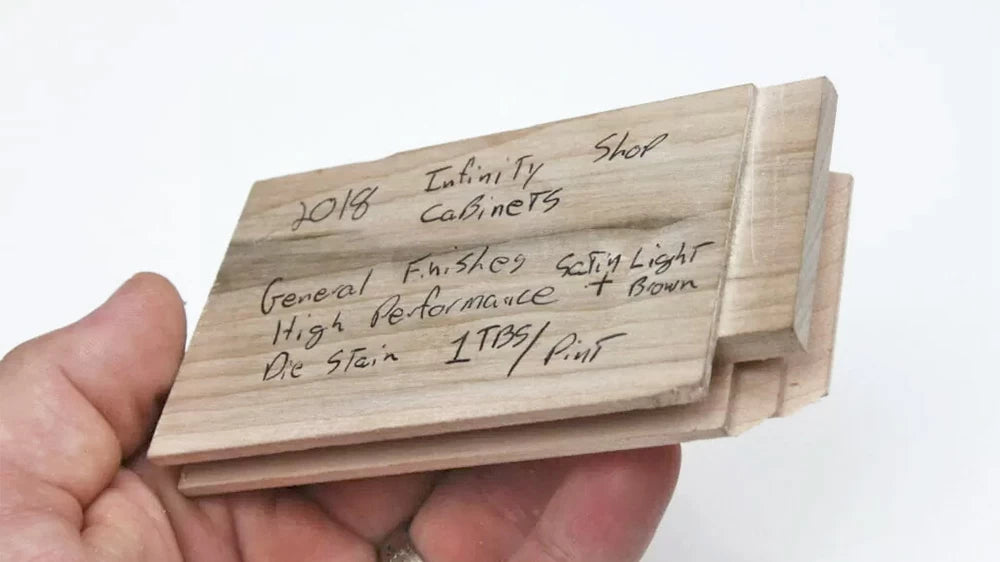

It is also not a bad idea to finish this piece to match the rest of the project so that you can use it to color match a new door if needed in the future. Note the details of the finish used including any custom finish mix recipe. I label this block in ink with the date, project name, and any other important info.

The physical dimensions of the block tell me everything else including thickness, width of the rail, material species, profiles, and so on. You can even go as far as to note the part numbers for the bits used. Once you have everything noted you can cut the block down so you don't have a full size rail. Think of this as a recipe a cook would use. With this one block I can "cook up" the same project over and over.